Introduction to Level Design for Games

Jon Hickenbottom shared his experience of studying the CGMA course Level Design for Games led by Emilia Schatz and the best level design lessons he’s learned.

Introduction

Hello, my name is Jon Michael Hickenbottom. I grew up in Ventura County, California where I currently reside. I am a Level Designer at New World Interactive and have helped to design levels for Insurgency, Day of Infamy, and the upcoming Insurgency: Sandstorm. With a desire to continually grow and sharpen my skill set, this past year I’ve sought out courses at CG Master Academy: modeling with Andres Rodriguez(Naughty Dog), foliage with Jeremy Huxley (Naughty Dog), and most recently, I completed the ten-week Level Design for Games course with Emilia Schatz (Lead Game Designer at Naughty Dog). Level Design for Games’ curriculum supplied me with heightened awareness, necessary terminology, more nuanced attention to detail, and greater confidence in my ability as a designer. The following is a breakdown of the workflow I followed, challenges encountered, and new understandings I hope to apply in all my future work.

Getting Started

Off the bat, this was my first time using both Unity and Maya to block out levels. Challenge accepted! Coming from a background in Source Engine and Unreal Editor, I had never used a modeling package to create layouts in this fashion. While nervous about how I’d adapt, I quickly discovered the speedy back and forth between Maya and Unity to be very helpful with making iteration and refinement of shapes in the scene painless. Furthermore, Unity was quickly generating collision automatically to help me get from blockout to playtesting within seconds. With Unity and Maya synced up, I was ready to get started!

Using Reference

An important first step for me is to find reference and inspiration. Google Images, Flickr, and Pinterest are always solid sources for image inspiration and direction. I enjoy discovering supplemental inspiration from art history books, cinematography, and “art of” books from various games. Assembling images into a mood board for assignments in either Pinterest or Photoshop kept me focused, and became a catalyst for creativity when encountering mental blocks along the way. The found images began to spark new ideas that may not have otherwise been considered.

For a section of the course, the theme was centered around the Wild West. I wanted to create a sense of scale, beauty, and risk within each of my levels. I tried to focus my reference search on shapes and spaces that could communicate this to the player. Inspiration was found in the remarkable art by William Henry Holmes, the thoughtful cinematography of Roger Deakins, the detailed environments in the Desperados series, the splendor of Westworld, and childhood memories of Back to the Future 3. One exciting discovery was remembering the photos I had taken on a summer trip to Zion National Park. These became great references for the shapes and aesthetic of the blockouts. Carrying around a camera or camera phone is a perfect way to easily build a personal reference library that you never know when will come in handy. It also serves in sharpening one’s eye for composition and framing!

Scale

For me, the scale is an important foundational pillar when starting any project or design. I’ve personally found becoming viscerally familiar with a project’s scale to be very important before moving too far into the process. As Jesse Schell says in The Art of Game Design, it is not important that 3D spaces have realistic 2D blueprints. All that matters is how space feels when the player is in it. With this course, being my first exploration into a third-person level design, I found myself constantly asking Emilia questions about proportions and scale.

With the mechanics of our third-person project template clearly defined, it was important to make sure the metrics were always consistent. In order to do this, I created a small collection of walls, doors, windows, cover, and objects that felt right in the game world and rounded their measurements to the nearest 1/4 meter. With these metrics established, I could snap to or duplicate the pieces as I blocked out my layouts.

Painting with Shapes

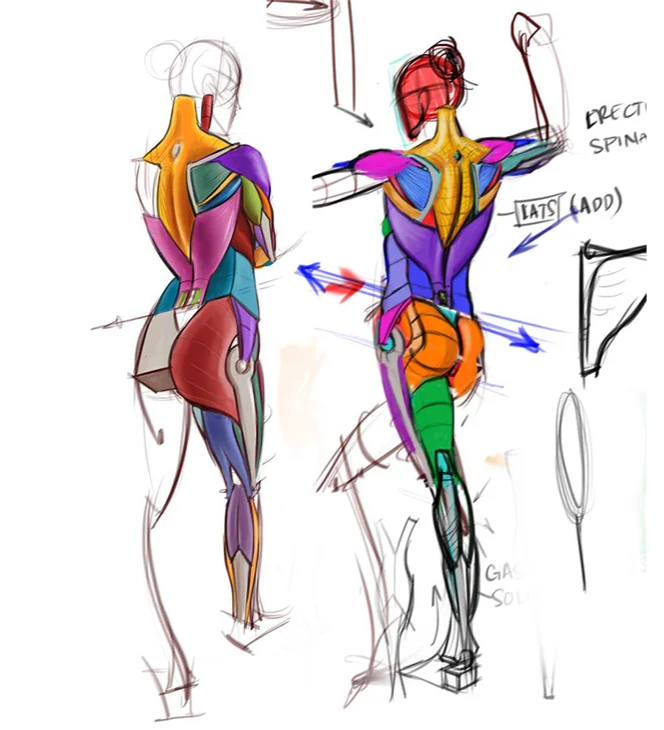

Emilia Schatz redefined my understanding of how to paint with shapes. I started a rough idea of my layout on graph paper, but I quickly jumped into Maya to get started.

Throughout the course, I challenged myself in these projects to be more comfortable off the grid and break from symmetry. With a background of level editors that encouraged the use of the grid for either organization or optimization, it was a refreshing endeavor to live comfortably off the grid, while still maintaining the use of metrics and proper scale. Living off the grid allowed me to thoughtfully paint shapes without restriction and limitation, thus focusing more on the artistic aspects of level design. This focus was freeing, and I could foresee the creative synergy that would occur between designers and artists as we move to understand the disciplines of one another. Within the past few years, I’ve sought to become a better artist in my pursuit to become a better designer. This course strengthened that pursuit. Through Emilia’s lessons, I began to appreciate the thoughtfulness required of each shape I created and each object I placed; not just from a level designer’s perspective but in how my choices could, in turn, affect a fellow collaborative artist’s workflow.

One wonderfully valuable tip was the power of the cube. I had always struggled to understand how complicated terrain and landscapes were created in games like Uncharted. Emilia introduced us to her use of the almighty cube. By squashing, stretching, and slicing a cube, the forms of various terrain elements begin to take shape. In moving these manipulated cubes within one another, it became clearer as to how to craft natural, seismic formations. The idea at this stage was not to worry about optimizing and welding vertices; it was more important to paint shapes, compose compositions, and create interesting spaces.

Composition

In week four, we began to explore composition from a single point of view. As referenced earlier, the practice of photography is an advantageous way not only to build reference but to continually focus design on composition, framing, and guiding the viewer/user. I’ve found it most valuable to spend ample time refining each composition. In the image above, I used the lines of my shapes to creating guiding lines that lead the viewer toward the structures near the middle. Using the angular lines of the rocks served as a helpful tool to guide the viewer.

Also, I worked to create some organization to the scene by removing any excessive noise within such a dense environment. For example, man-made structures on the right are balanced with the layered rocks on the left, and groups of colors separate rocks, foliage, water, structures, and sky. Finally, keeping in mind the rule of thirds and Rudolf Arnheim’s idea of “structural skeletons”, I worked diligently to be thoughtful with every shape I placed. Being attentive to these ideas of psychology helped me create magnetic-like areas of pull and attraction to guide the viewer’s field of vision and movement. Through Emilia’s teachings and dissection into the psychology of a composition, I feel I gained a renewed appreciation for its nuanced power in design, and consider it a key tool in a designer’s toolset.

Landmarks & Internal Compass

While much has been told about Naughty Dog’s impeccable use of Disney’s “weenies” in the context of games, Emilia reminded us to not limit our thinking of these focal elements as only distant structures and shapes. These landmarks can also be local features to help strengthen the user’s mental map of your spaces and spatial compositions. It was such a great reminder to understand that landmarks can be both local and distant to help the player traverse your spaces subconsciously. As I began to block out the levels within the course, I found ways to employ landmarks—both local and distant—to better serve the player’s internal compass. For example, a large tower looms in the distance enticing players to continue exploring, while a water fountain in front of you reminds you of what part of the small market you are currently inhabiting.

Crafting Districts & Nodes

As we moved from singular areas to large spaces, Emilia introduced us to the idea of nodes, edges, and districts. As I began to map out my level, I began to discover the points of intersection— these are considered nodes. Nodes can be described as intersections and decision points within your paths. They also become great positions to form your compositions around. We can be certain the player will circulate through these points, and therefore be perfect for framing your compositions. Emilia encouraged us to set up various cameras to keep our focus on shaping and refining strong compositions at these points.

Edges help communicate that you are entering into a new space. These can be thought of as linear elements that help divide one area from another. I tried to place these around various districts within the level. For example, a grand wall and gate at the entrance help communicate the borders of the town, a small fence shows where a graveyard starts, and a large archway was placed to divide the market area from a military camp.

Finally, building your spaces to include identifiable districts helps promote identity and contrast within your levels. It also allows for interesting points of connection between spaces.

Bringing all the elements together, the following image shows some of the various district identities I tried to communicate: a marketplace, jagged graveyard, elevated upper class, separated lower class, and the nature surrounding all of these. By employing compositions at these nodes, structuring identifiable edges, and creating distinct districts, I hoped to implement a spatial composition the player found interesting to explore, discover, and inhabit.

Bringing It All Together

In the latter weeks of the course, our assignments began to marry past lessons together and we were introduced to third-person combat as shown above. Through a familiar process of making decisions, crafting blockouts, testing, and iterating, it became exciting to see our small scenes grow into full-fledged spaces, filled with distinctive districts, environmental storytelling, engaging combat, and an established narrative to bring it all together.

Conclusion

This course provided me with a masterclass of knowledge that I’ve only scratched the surface on here. I’ve found a renewed outlook on crafting levels with intentional shapes and heightened shape language. It continually stretched and challenged me as a designer, and helped me build sturdy confidence in tools, perspectives, and genres I had never explored before. I learned how to trust myself more,and free myself to create designs that expressed what was true to my heart.

I count myself fortunate to have learned from Emilia Schatz. Her constructive feedback never wavered, and what she shared was always what I and the class needed to hear most. I encourage anyone—at any experience level—to take this course. It has fundamentally changed how I will approach level design.

I highly recommend CG Master Academy and especially Level Design for Games with Emilia Schatz.

Thank you for reading. I hope what I have to share helps you!